Photo by Layne Kennedy

For a true Up North experience, look no further than the Boundary Waters — and the gateway communities that offer access to its breathtaking million-plus acres.

If you’re a Great Lakes trailerboater, or any Midwesterner with a bent for watersports and the great outdoors, chances are you’re familiar with Up North — that vast country stretching from northern Minnesota, across Wisconsin and Michigan, to eastern Ontario. Like a magnet, it draws the region’s population into its embrace throughout the summer months, the fall color season, during holidays and on snowy winter weekends.

As you drive north from Minneapolis-St. Paul, Chicago, Milwaukee and Detroit, the suburbs gradually peter out amid rolling farm country with increasingly thick copses of woodland. Drive farther, and the woods get bigger, deeper, darker and cooler, and their sheltering arms harbor countless glimmering inland lakes. The air seems fresher, and the wind carries the eerie call of a loon.

Of course, those woods are pockmarked with second homes, hotels, rental cabins and various businesses catering to the tourist trade, but if you know where to look, you still can find a true wilderness experience, one that the original native peoples still would recognize centuries after their birchbark canoes first paddled these waters.

Nearly 1.1 million acres in size, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness extends almost 150 miles along the U.S.-Canada border in northeastern Minnesota, in the northern reaches of the state’s Superior National Forest. It’s part of an even greater tract of boreal wilderness, as it lies adjacent to Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park and abuts Voyageurs National Park in the west.

This is true wilderness, a primeval, glacially sculpted landscape of towering cliffs and granite rock formations, plunging canyons, cascading waterfalls, ancient pine forests and more than 1,000 pristine lakes and streams, with countless emerald islands, hidden coves and sheltered bays.

Pictographs are visible on some rock faces. The Ojibwe, who settled in the area when the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota nations moved west, consider this to be their historic homeland. Many still reside on the nearby Grand Portage Indian Reservation.

Photo by Ken Martinson

Works of Art

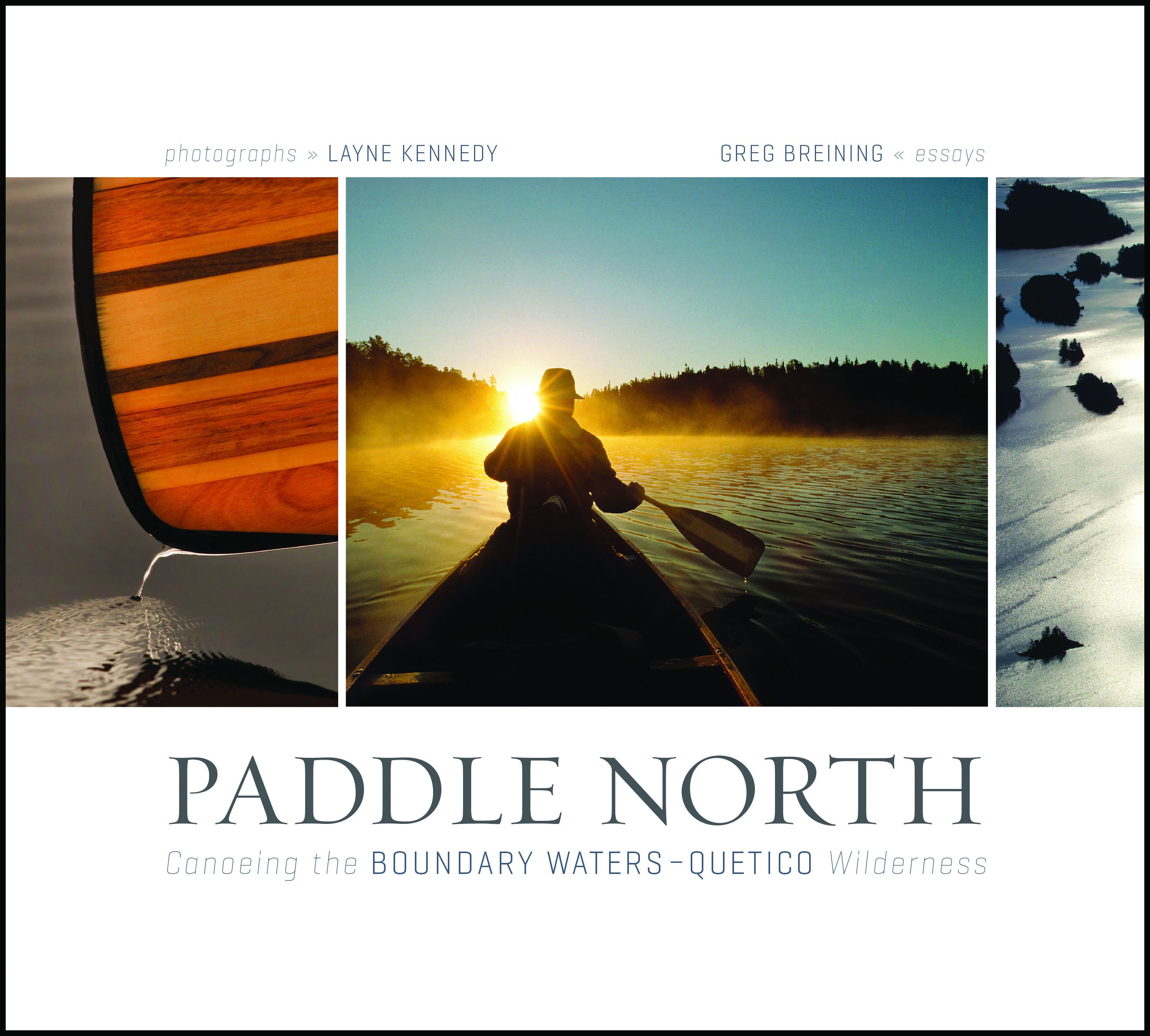

Few people have captured the spirit of the Boundary Waters better than Minnesotan Layne Kennedy. A fine art photographer known for his editorial magazine work, Kennedy has photographed stunning places all over the world — including Minnesota’s Boundary Waters.

Few people have captured the spirit of the Boundary Waters better than Minnesotan Layne Kennedy. A fine art photographer known for his editorial magazine work, Kennedy has photographed stunning places all over the world — including Minnesota’s Boundary Waters.

In his most recent book, “Paddle North,” published in 2010, Kennedy provides a unique view into life in this remote and pristine Up North region, stretching into Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park. Kennedy’s 2008 publication, “A Hard-Water World” takes a whimsical look at ice fishing.

Both books are published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press (shop.mnhs.org) and are available for purchase through the publisher, as well as Amazon.com and fine bookstores throughout the country. Individuals desiring signed copies can make a personalized request on Kennedy’s website (www.laynekennedy.com), or send him an e-mail at: lk@laynekennedy.com.

Photo courtesy of Cook County Visitors Bureau

Rich history

French explorers and fur traders were the first Europeans to travel through the Boundary Waters, starting with explorer Jacques de Noyon in 1688. By the late 1700s, the Hudson’s Bay and North West fur-trading companies competed intensely here. Water was their lifeline, and today’s international border in the Boundary Waters mirrors one of the voyageurs’ most popular paddling routes.

Due to its remote location, the region was spared serious efforts to exploit its natural resources until the turn of the 20th century. Industrial interests sought to open the wilderness for mining, logging and even dam projects.

Recognizing the need to preserve the character of this unique area, the U.S. Forest Service created the Superior Roadless Area in 1926. The 1964 Wilderness Act officially formed the BWCAW, a legal unit of the National Wilderness Preservation System, and the 1978 Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act established the lake usage, portage and permit regulations that approximately 200,000 annual visitors observe today.

Logging officially ended in 1979, and the BWCAW became a haven for its indigenous flora and fauna, as well as for the intrepid adventurers who seek solitude, peace and an authentic communion with nature. Today, it boasts nearly 2,200 designated backcountry campsites, 12 hiking trails and more than 1,500 miles of paddling routes for canoeists and kayakers, thanks to the extensive network of interconnected lakes, streams and portages.

More than 10 years ago, National Geographic named the Boundary Waters one of its “50 Places of a Lifetime,” and when the magazine released a special iPad app this year, the BWCAW remained on the list. It’s one of Minnesota’s top tourist attractions, and visitors come from all over the world, in every season.

Clearly, if you’re an Up North enthusiast, this is a distinctly Midwestern delight you don’t want to miss.

And if you’re a powerboater who’s keen to head north with a trailer, don’t worry. While more than 75 percent of the wilderness area is set aside for nonmotorized use, powerboats are allowed on a few lakes and have a range of BWCAW entry points available. Little Vermilion Lake, Loon Lake and Loon River have no horsepower limits; Lac La Croix also is unrestricted, provided you don’t venture beyond the south end of Snow Bay on the U.S. side.

If your power plant doesn’t exceed 25 horsepower, your options open up to include Fall, Moose, Newton, Newfound, East Bearskin, Sucker, South Farm, Snowbank and Trout lakes. If you’re at 10 horsepower or less, you also may use Clearwater Lake, North Fowl Lake, South Fowl Lake, Seagull Lake east of 3 Mile Island and portions of the Island River.

Motors may not be used, or even kept on board, when you’re on a paddle-only lake. If you’re a sailor or sailboarder, bear in mind that these rules apply to mechanized craft as well; if the rules say paddle-only, make sure you’ve got a canoe or a kayak.

In fact, paddling through the Boundary Waters is perhaps the best way to experience the wilderness area, as it puts you in vivid, intimate touch with the world of the Ojibwe and the voyageurs. Just think: No motors, no electricity, no phone lines, no cell towers and no roads.

“Early in the morning, the sunlight is clean and clear,” said Karla Wotruba of Appleton, Wisconsin, who travels to the BWCAW with five women friends each year for a girls-only paddling adventure. “There is a mist on the water, and the water is like a mirror to the sky. Islands appear to float on their reflections. Other times, sunlight ripples across the surface. I never get tired of that picture, and I can never capture it with a camera. (It’s) like diamonds scattered across of the water.”

Photo by Erin McCann

Planning your trip

Like Wotruba’s group, many visitors will plan their own trips through the BWCAW. If you’re one of these, remember that permits are required for all overnight visitors, whether you’re hiking, paddling or using your powerboat. From May 1 to September 30, when the Boundary Waters sees its heaviest use, you’ll need a quota permit in advance. From October 1 to April 30, self-permitting is accepted at the wilderness area’s various entry points.

If you’ve never been to the BWCAW, however, or if you’re a newbie when it comes to backcountry adventuring, enlisting the services of a local outfitter is the best way to go. Not only will they set you up with the right gear and provisions, they’ll also help you plan the best route based on your experience and wishes. Some provide guided trips as well.

Every seasoned BWCAW paddler has his or her preferred routes and camping spots, as there are literally hundreds from which to choose. Wotruba said she keeps a journal so she can remember her favorites.

“The Phoebe River and Kawishiwashi River reveal themselves as you paddle, each turn showing more and more spectacular scenery,” she recalled. “One of the days required a lot of portages — 12 in one day. The last time we went that route, the path for a portage went right through a creek and across the top of a small waterfall.”

Wotruba acknowledged that it’s not always easy going. She recounted portage paths that were completely submerged, where the only way forward was through. She said beavers can change a river that was easily navigated just days before. She remembered passing over and under downed trees, using a canoe as a bridge for passing packs and paddles, using paddles as prods to test the security of marshy ground and crawling down a path-come-cliff to Chaser Lake.

And, sometimes, maps are deceiving.

“A marshy river can dry up and take hours to paddle and scoot across,” she said. “The twists and turns can go on and on. Long portages can be flat and easy or covered with water. Short ones can be rock-strewn and treacherous. We may think we know what’s on the map, but we can’t control it.”

So stay flexible, and focus on the present.

“A lot of times, I’m not sure what the lake is named, or how many portages are left, because I have to live in the moment,” Wotruba reflected. “I can’t worry about what is coming next; I can only deal with right now.

“(And) nature has the final word,” she added. “One year, we were absolutely socked in by the wind. The next morning it was glass.” Then come the moments of pure magic, where time completely falls away.

“Last year, we had a portage onto Stuart Lake that was old-growth pine trees along a stream and waterfall,” Wotruba said. “The trees were enormous, creating a canopy over our heads, trunks as wide as whiskey barrels, and the path was rust-colored with pine needles. Realizing how long those trees have stood by that path, I felt as though I were walking in ancient footsteps.”

Gateway communities

Wotruba’s group is familiar with all three principal gateway cities to the BWCAW: Grand Marais, Tofte and Ely, Minnesota. From Grand Marais, the women travel the historic Gunflint Trail, which stretches 57 miles from Lake Superior’s north shore to Saganaga Lake in the wilderness area. On the way, they stay at the Tuscarora Lodge and Outfitters in a bunkhouse.

“It’s very rustic, just bunkbeds stacked three high,” Wotruba noted. “On our way, we’ve eaten dinner a few times at My Sister’s Place in Grand Marais, which is special for our all-girl group.”

Also on the Gunflint Trail is Clearwater Canoe Outfitters and Historic Lodge, the area’s oldest and largest freestanding, hand-hewn whole-log structure. Charlie and Petra Boostrom bought the property in 1914; convinced that their spot on Clearwater Lake had the finest view on the Gunflint Trail, the Boostroms started the lodge in 1915.

It was the first resort and outfitter on the trail, and it remains the only resort on Clearwater Lake. The main lodge building was finished in 1926; four of the cabins and the sauna also are original buildings.

Here, guests will enjoy the same breakfast recipes used 90 years ago, as the cook and kitchen manager is a granddaughter of the couple that founded the business. In addition, the founders’ daughter, who was born in the lodge in the 1920s, comes weekly to tell stories around the fireplace.

Where to stay

While not an outfitter, another distinctive lodge in the area is the Cross River Lodge, formerly the Moosehorn and originally the Borderland. Located on well-known Gunflint Lake, the lodge was built in the 1920s and still boasts its original native stone fireplace.

The current owners have extensively remodeled this small resort to bring back its true northwoods feel. Guests may choose lodge-suite or cabin accommodations.

Then, back in Grand Marais, there is Bear Tracks Outfitting Company on Highway 61, which provides outfitting services as well as sea kayak rentals, fishing charters and year-round lodging. Bear Tracks can provide full and partial outfitting, including provisioning, and the night before or after your trip, you can enjoy lodging in rustic cabins at Bally Creek.

In business for nearly 40 years, Bear Tracks can support kayaking and canoeing adventures in the summer and cross-country skiing trips in the winter.

If you have a little time to spend in Grand Marais before or after your BWCAW exploration, enjoy a frosty beverage and water views at the Gunflint Tavern and stop at the Trading Post to peruse the selection of camping gear, clothing and household items. And if you’re going to be in the area for a while, the North House Folk School offers classes such as boatbuilding, snowshoe making and timber framing.

While Grand Marais is gateway to the Gunflint Trail, the easternmost access route to the Boundary Waters, the little community of Tofte — between Taconite Harbor and Lutsen on Lake Superior’s north shore — provides access to the Sawbill Trail. It also features the Bluefin Bay Resort, where visitors can savor fresh Lake Superior fish at the Coho Café.

“We’d stay at the AmericInn if we were going out through Sawbill Outfitters on the Sawbill Trail,” Wotruba said. “In 2009, we had dinner at the Coho Café, and I’m still dreaming about their smoked marinara sauce.

“For many years, when we came out of the Boundary Waters, it was a special treat to eat our first breakfast at the Bluefin Grille,” she continued. “They have oatmeal with wild rice that was spectacular. Someday I’ll skip the camping and just stay at the resort. As long as I put some mud on my clothes, no one needs to be any the wiser!”

Finally, there is Ely in the west, gateway to the Echo and Fernberg trails. Wotruba said her group frequently stays at a budget motel there called the Paddler’s Inn.

“We’ve rented canoes for many years from Piragis Outfitters and enjoy browsing through all their clothing and gear, trying hard to remember that the camping experience means leaving some of the amenities of home behind,” she commented. “We usually have a wonderful last dinner at the Chocolate Moose before heading out in the morning.”

“The Chocolate Moose is right in town and has wonderful food,” agreed Erin McCann of San Diego, California. “Save room for dessert! My favorite is their strawberry rhubarb pie.”

Few outsiders know the community better than McCann, who grew up in Mequon, Wisconsin, and worked for years as an Ely-based instructor with Outward Bound. The organization offers year-round guided trips into the BWCAW.

“The Echo Trail has many Boundary Waters put-in points,” she commented. “A good one is at Hegman Lake, where you can take a short paddle, ski or snowshoe to the pictographs.” An outfitter’s extensive knowledge of the area and equipment will add immensely to the pleasure of your trip.

One such operation is Canadian Waters Inc. Founded by the Waters family in 1964, the company has been under continuous ownership and management longer than any other Boundary Waters and Quetico outfitter; its headquarters covers half a square block in downtown Ely. They are the only outfitters selected to outfit the families of two sitting U.S. presidents.

Home to both its BWCAW canoe outfitting business and retail store, Canadian Waters offers everything you need for a paddling and wilderness camping adventure. And, in addition to camping equipment, you’ll also find fishing gear, outdoor clothing and gift items.

If you’re not paddling, McCann advised that summer and fall are great times for drives up the Echo Trail, which will take you deep into the forest along the BWCAW boundary. Another good choice is Highway 1. The sights, she said, will blow you away — from the endless views of lakes, rivers and forest to witnessing a moose, wolf or loon in its natural environment.

Exploring in town

The town is fun, too. If you’d like to stay for a night or two before or after your paddling trip, check out the Blue Heron Bed and Breakfast, the Grand Ely Lodge and the summer-only Burntside Lodge, all of which are on lakes that allow powerboats.

You also might want to check out Northern Grounds for coffee and breakfast or panini sandwiches, and the Boathouse Brewery for burgers and pizza. Several restaurants have open mic nights during the summer, and a couple have outdoor patios for live music and dancing.

A final tip, according to McCann: Visit the porch at the Grand Ely Lodge, where you can enjoy a glass of wine or a cocktail and watch the sun set over the lake.

Ely, she observed, is really like no other place in the world. “The locals are some of the nicest people you’ll meet,” she said. “In the summer, 90 percent of the cars have canoes strapped to the top, and in the winter, there are more snowmobiles than cars on the streets.”

Indeed, winter is an adventurous time of year to visit the BWCAW and surrounding communities. Popular activities include snowmobiling, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, ice fishing, skating and dog sledding.

“If you want to try dog sledding, several companies offer trips from a couple of hours to several days long,” said McCann, who is an accomplished dog-sled guide.

She recommended Outward Bound and White Wilderness Sled Dog Adventures. Outward Bound offers winter camping and dog sledding adventures from four days up to several weeks in length. White Wilderness features a variety of trips, from day outings to more elaborate yurt-to-yurt overnight tours.

And don’t miss Ely’s Winter Festival in February. Snow carvers from around the world converge on Whiteside Park, which overflows with professionals’ and locals’ artistic efforts. The fun continues with the Mukluk Ball, live music, ski racing, dog sled rides and a variety of family events.

No matter when you visit the Boundary Waters, however, you can rest assured that it will be a one-of-a-kind adventure to remember. “I’ve seen a moose swimming across the lake in front of me,” Wotruba said. “We’ve had (nesting) turtles crawl right up to the campsite as we watched the moon rise over the water. There are times when we are paddling along, and no one says a word. All you can hear is the slipping of the paddles in and out of the water and the canoes gliding along.

“I used to be so grateful for all of the creature comforts when I returned home, but now, I sometimes think if we wouldn’t run out of food, I could stay,” she mused. “Time in Boundary Waters is precious, and the trip home is always bittersweet.”